65

hawkers at public gatherings, or by

holiness evangelists. But it was com-

mercially introduced to the larger

American public in the 1920s through

the recordings and radio perform-

ances of such people as Smith's Sacred

Singers, Rev. Andrew 'Blind Andy'

Jenkins and his family, Rev. Alfred

Karnes, and the Phipps Holiness

Singers. Since that time the tradition

has been well represented in commer-

cial country music by such musicians

as the Blue Sky Boys, the Bailes Broth-

ers, the Louvin Brothers, Mac O'Dell,

Martha Carson, the Johnson Family

Singers, the Masters Family, and the

Lewis Family. While their approach

has differed in many particulars from

the groups just mentioned, the Chuck

Wagon Gang remains America's most

important representative of folk

gospel music, and a valuable link be-

tween the world of the formal quar-

tets and country music.

W

hen the Chuck Wagon Gang

launched its career in 1935,

the distance between the society of

which they sang and the one in

which they actually lived was not

yet an overwhelming one. Theirs

was a Texas that was still basically

rural, with an economy dominated

by cotton farm tenantry, and with

a population little more than one

generation removed from residence

in the older Southern states. The oil

boom presaged Texas's future; it

did not yet dominate its present.

Roman Catholicism was a powerful

presence in the southern part of

the state, particularly among Mexi-

can-Americans, but for the great

majority of other Texans, black and

white, church preference inclined

toward the evangelical and funda-

mentalist

groups:

Baptists,

Methodists, Campbellites, and Holi-

ness. For such people the brush

arbor revival and the singing con-

vention, with its dinner-on-the-

grounds — an all-day music convo-

cation held in a church or county

court house and marked by a sump-

tuous picnic to which all con-

tributed their special dishes — were

not quaint remnants of a frontier

society, but were instead vital and

cherished aspects of community

life.

The worst days of the Great Depres-

sion had subsided, but hard times still

prevailed. Many Texas families had

seen husbands, fathers, or sons (and

sometimes daughters) hitting the

road to find employment, and more

than a few had become part of that

large stream of California-bound

migrants, the Okies, who journeyed

west on Route 66. Nevertheless, most

people stayed at home, clinging more

tightly than ever to its familiar secu-

rity. Inexpensive entertainment such

as radio, therefore, experienced a

golden age, and Texans were second

to none in their reliance on the

medium. Devotees of homespun

music (black and white, secular and

gospel) could hear live entertainment

throughout the day, especially early

in the morning and at noon, on Satur-

day nights from the radio barn

dances, and late at night over the

Mexican border stations. Radio per-

formers hoped for wider exposure

and an opportunity to move beyond re-

gional identification. Some managed

(

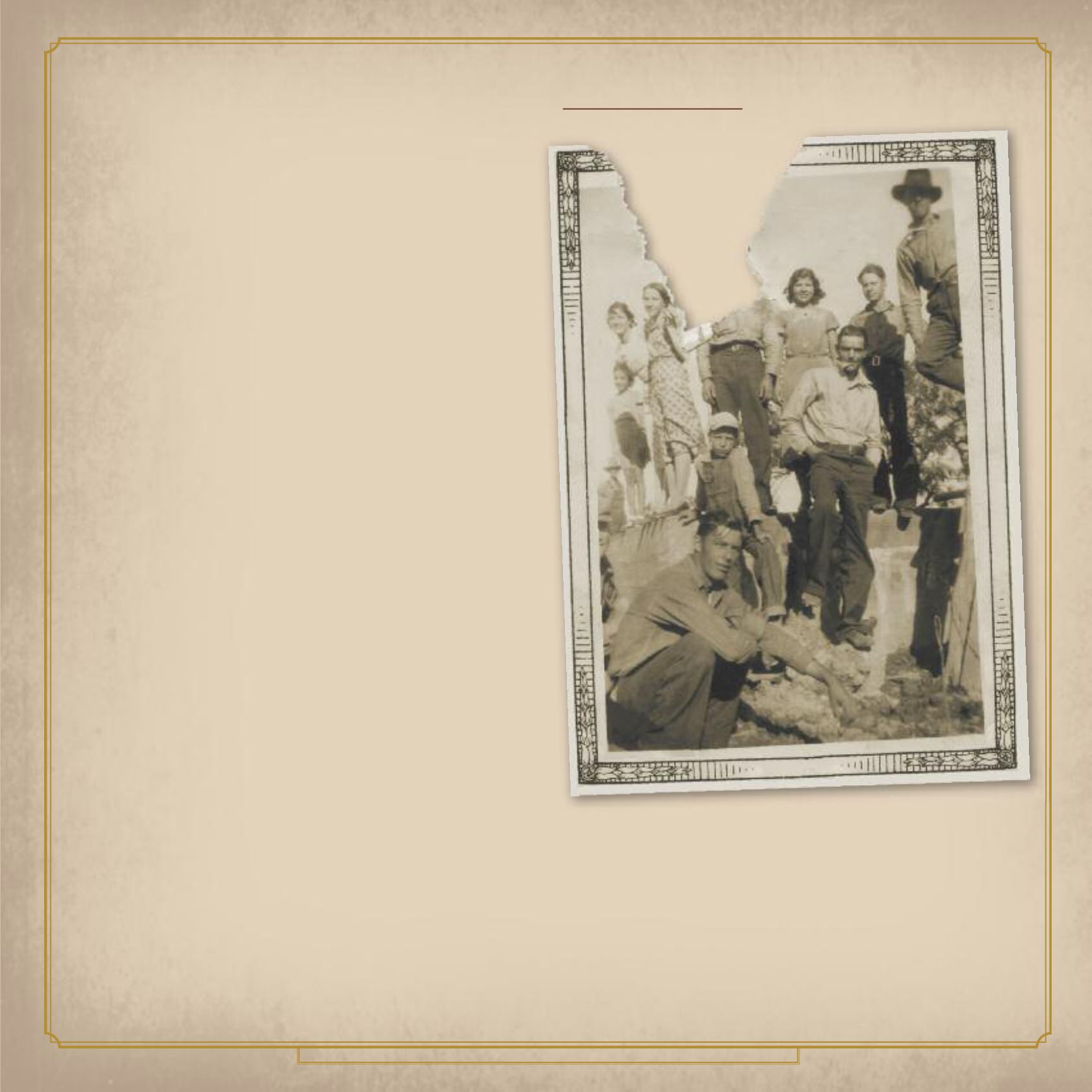

BELOW

) An early photo of some of the Carter children

and other unknown people. This photo was likely taken

in the late 1920s. The other people probably worked in

cotton just as the Carters did at this time.