Wer war/ist Nelson, Willie & Kimmie Rhodes ? - CDs, Vinyl LPs, DVD und mehr

Born on 30 4th 1933 in Abbott, Texas, USA.

Willie Nelson played as a child and teenager in country bands. He is one of the biggest stars of the genre at all and was represented until today with over 100 singles on the U.S. country charts. Following the release of his debut 45er 'Lumberjack' in 1956, he moved to Nashville, where he sold his own demos and thus ushered in his career authors. In 1961 he played with Ray Price at the Cherokee Cowboys.

He wrote his first hits for Roy Orbison, Patsy Cline and Faron Young. Nelson settled after his marriage to Shirley Collie as a pig farmer in Ridgetop, Tennessee, down. He stepped up today with stylistically different colleagues such as Bob Dylan, Carlos Santana, Neil Young and Julio Iglesias in duet on.

With Johnny Cash, Waylon Jennings and Kris Kristofferson he plays in addition to his solo career, under the name of The Highwaymen. 1978 founded his own label, Lone Star. Nelson was the early 90s with around $ 16 million debt to the IRS in the Cretaceous. 1991: marriage to Annie D'Angelo. The number of Nelson rehearsed songs beyond the 1000 mark.

From the Bear Family Book - 1000 pinpricks of Bernd Matheja - BFB10025 -

Willie Nelson

1964 through 1972 were eight of Nashville’s more unsettled years.The pop-oriented ‘Nashville Sound’ pioneered by Chet Atkins and Owen Bradley had been adopted by much of the industry. In the late 1950s, after rock ‘n’ roll knocked the entire Nashville music industry off its shaky foundation, that smoother, more sophisticated sound had saved Nashville by expanding country records to grab pop record buyers. It made Don Gibson, Jim Reeves and Patsy Cline greater stars than they’d been singing hard country alone. By 1964, that initial rush of creativity had slowed. Plane crashes claimed two top exponents, Cline in 1963, Reeves in the summer of 1964. At that point, Eddy Arnold, whose string of massive hits diminished in the wake of Elvis, was about to make a dramatic comeback with elaborately orchestrated ballads like Make The World Go Away, light years from the intimate dignity of his 1940s hits. Ray Price had already begun to occasionally wrap a string quartet around the Cherokee Cowboys on many of his recording sessions, attracting new fans but sending many older ones stomping off in disgust.

Not even a honkytonk giant of George Jones’s stature was immune from Nashville sound production. Onstage, it was Texas honkytonk business as usual, the fiddle and steel whining behind him. The recording studio was another matter. Pappy Daily, his discoverer and only producer, forced Jones into the softer mold at United Artists and later at Musicor Records. He continued in that mode with Billy Sherrill after joining Epic in 1970.

A few wild cards counteracted the syrupy side of things, since the country audience divided as it expanded. As Price slithered out of his rhinestone skin into tuxes, a West Coast honky-tonk cyclone, unstoppable as the dust storms that drove Texans and Okies to California in the first place, roared out of Bakersfield. The success of Buck Owens, followed by the rise of Merle Haggard, reflected the belief of many fans that some of the pop stuff was going too far afield, that Nashville needed an alternative. A second alternative came from within Music City with the rise of Johnny Cash. Popular for nearly a decade, his no-frills music and phenomenally successful 1967 ‘Folsom Prison’ LP weren’t as surprising to Nashville as his acceptance by pop audiences.

On 16th Avenue South, Atkins and Bradley continued setting the pace. At Columbia, Don Law was retiring, and though Bob Johnston was his immediate successor, the label’s rising star was clearly Billy Sherrill, the former R&B musician and Sam Phillips’ engineer who took over much of the production for Columbia’s Epic subsidiary. Nearly all Nashville producers saw the softer sound as the strongest and simplest formula for putting across a new artist quickly. It explained why artists were counseled to trust their producer, who usually picked material (unless the singer was one potent writer) and offered ‘direction’. If a producer happened to have written some of the recommended songs, or at least own an interest in publishing songs they pushed on artists, it was a conflict of interest routinely winked at around 16th Avenue South.

There was one huge problem. Assuming that one sound could fit any singer was an idea that didn’t always work out in practice. Convincing the men in the control room that ooh-aah choruses and muted strings just didn’t work with everyone was quite another matter.

That was the world Willie Nelson faced in 1964.

At 31, he was one of Nashville’s top writers, whose songs had been hits for many, including Patsy Cline, Billy Walker and Faron Young. Like other writers of his generation, Harlan Howard and Hank Cochran among them, his recording career had been less impressive. He’d started his singing career before Hank Williams died. His early recordings in Washington State and Houston went unnoticed. Only after moving to Nashville in 1960 and crafting such standards as Crazy, Funny How Time Slips Away and Hello Walls did he land a major label deal with Liberty. After a Top Ten duet single and a solo Top Ten hit, both in 1962, his success on records quickly faded while he continued writing brilliant songs for others.

At 31, he was one of Nashville’s top writers, whose songs had been hits for many, including Patsy Cline, Billy Walker and Faron Young. Like other writers of his generation, Harlan Howard and Hank Cochran among them, his recording career had been less impressive. He’d started his singing career before Hank Williams died. His early recordings in Washington State and Houston went unnoticed. Only after moving to Nashville in 1960 and crafting such standards as Crazy, Funny How Time Slips Away and Hello Walls did he land a major label deal with Liberty. After a Top Ten duet single and a solo Top Ten hit, both in 1962, his success on records quickly faded while he continued writing brilliant songs for others.

Song royalties gave Willie a farm in Ridgetop, Tennessee, northwest of Nashville, where he played the eccentric artist, living with an extended family, sustained by writers’ royalties and frequent touring. That would have satisfied many. But he still believed he had potential as a singer if someone gave him a chance. He still wanted to record, knowing he had it in him to succeed, even if many in Nashville regarded his weird vocal phrasing and unconventional attitude, disdain for spangled suits and mile-high pompadours, as a bit off base.It wasn’t like a successful, eccentric songwriter couldn’t become a recording star on his own terms. In 1964, Willie’s longtime pal Roger Miller had done just that, scoring big with Dang Me and Chug-A-Lug that year after unsuccessful stints on Mercury, Decca and RCA. King Of The Road in 1965 would take Roger far beyond the country crowd.

Willie spent a brief two-session period with Monument in 1964 before beginning eight years with RCA. Over those years, he’d enter the RCA Nashville studios for 44 solo sessions. Guitarist Chet Atkins, RCA’s Vice President in charge of Nashville Operations, probably understood unconventionality better than just about anyone in Nashville at the time. He appreciated Willie’s uniqueness. His challenge was to sell Nelson to a wider audience by integrating that uniqueness into the usual trends to make it acceptable, just as he had with Gibson and Reeves.

In Willie’s case, Atkins admittedly didn’t do very well. During those years, with himself or Felton Jarvis producing, a total of 15 Willie Nelson RCA singles charted, only two, One In A Row in 1965 and Bring Me Sunshine in 1968, breaking into ‘Billboard’s’ country Top Twenty. Eight of his LPs made it to the magazine’s Top Country Albums chart, only three rising into the Top Ten. At the time, the only area Willie enjoyed consistent popularity with his records was his home state of Texas.

Those eight years would leave the singer frustrated, a frustration that would ferment and expand, drilling into his mind the idea that he could produce better records on himself than anyone in Nashville could. He was not alone among RCA artists sick of the label’s assembly-line approach. His friend and fellow RCA artist Waylon Jennings, another who’d enjoyed only moderate success, had a similar idea. In the mid-1970s, Nashville would call it ‘Outlaw’, then act as if it were their idea all along and package old Waylon and Willie material with newer recordings. They’d also give country music its first platinum LP with the 1976 release ‘Wanted! The Outlaws’. Today, it's easy to see he and Waylon were right, and just as easy to blame Atkins and Jarvis for not knowing how to produce either one.

Those eight years would leave the singer frustrated, a frustration that would ferment and expand, drilling into his mind the idea that he could produce better records on himself than anyone in Nashville could. He was not alone among RCA artists sick of the label’s assembly-line approach. His friend and fellow RCA artist Waylon Jennings, another who’d enjoyed only moderate success, had a similar idea. In the mid-1970s, Nashville would call it ‘Outlaw’, then act as if it were their idea all along and package old Waylon and Willie material with newer recordings. They’d also give country music its first platinum LP with the 1976 release ‘Wanted! The Outlaws’. Today, it's easy to see he and Waylon were right, and just as easy to blame Atkins and Jarvis for not knowing how to produce either one.

Would Willie have fared any better at any other major label in those years? That’s doubtful. Atkins correctly characterized Willie as being “ahead of his time.” From 1964 through 1972, Nelson hadn’t a snowball’s chance in hell of being understood anywhere but Texas. Today, the world understands the Lone Star State’s quirky musical eclecticism at the heart of Willie’s repertoire. 30 years ago, few outsiders and most of Nashville didn’t get it at all. True, Nashville accepted Texas singers, but ignored the culture that produced them, preferring to shove them into the mold.

That’s why it isn’t likely that results would have been any better for Willie artistically or commercially, had he been recording with Don Law at Columbia, for Ken Nelson or Marvin Hughes at Capitol, for Billy Sherrill at Epic, Owen Bradley at Decca or Jerry Kennedy at Mercury. The only Nashville producers in that era who stood a remote chance of understanding him would have been mavericks like Bob Johnston, who produced Johnny Cash at Columbia or Jack Clement, with his lifelong flair for the unconventional. Would an independent label have been the answer? Hardly, given the non-results during his brief stay at Monument.

Taken in the context of that era, Willie didn’t break a couple of Nashville rules. He broke a slew of them. At RCA, production of his records was usually formulaic even if his songs were unconventional. While recording his own tunes wasn’t a reach, at RCA he laid down a crazy quilt of material, mostly Nelson originals with country and pop standards mixed in. He occasionally covered others’ hits, with a few contemporary pop and rock songs and whatever else he liked thrown in for good measure. After he became an established force in both country and popular music, Willie’s varied repertoire and musical settings would be viewed as marvelous eclecticism. When he was recording for RCA, such variety was seen as eccentric at best.

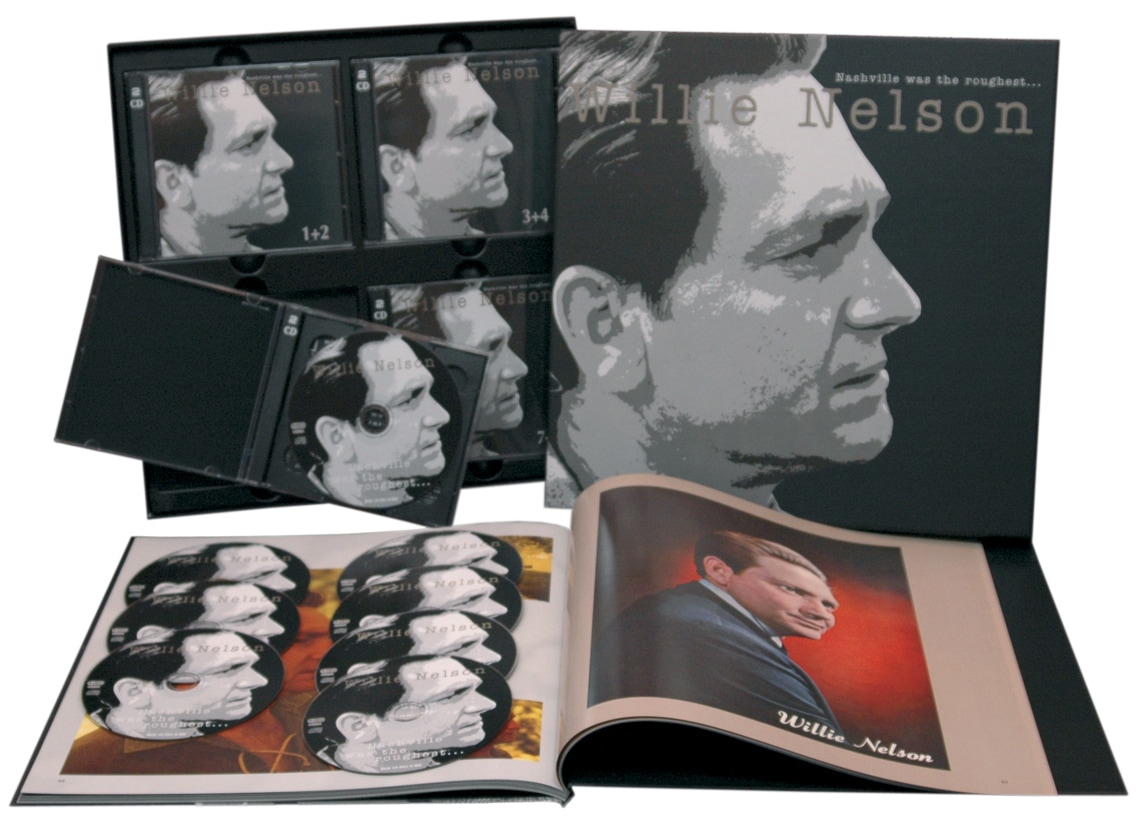

Willie Nelson Nashville Was The Roughest..(8-CD)

Read more at: https://www.bear-family.com/nelson-willie-nashville-was-the-roughest..8-cd.html

Copyright © Bear Family Records

Copyright © Bear Family Records® Alle Rechte vorbehalten. Nachdruck, auch auszugsweise, oder jede andere Art der Wiedergabe, einschließlich Aufnahme in elektronische Datenbanken und Vervielfältigung auf Datenträgern, in deutscher oder jeder anderen Sprache nur mit schriftlicher Genehmigung der Bear Family Records® GmbH.

Weitere Informationen zu Nelson, Willie & Kimmie Rhodes auf de.Wikipedia.org